Hoping to turn ‘supply and demand’ economics on its head, at the request of the major record labels Apple has introduced ‘variable pricing’ to the iTunes Store.

Hoping to turn ‘supply and demand’ economics on its head, at the request of the major record labels Apple has introduced ‘variable pricing’ to the iTunes Store.

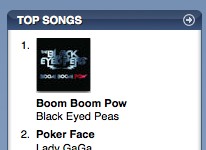

Under the new pricing structure, announced back in January at Macworld, tracks cost either 69 cents, 99 cents or $1.29, depending on their popularity. Or as the LA Times recently reported:

True to supply-and-demand economics, the price of music downloads will be geared to the artist’s popularity. Releases from new artists would receive the lower pricing, while tracks from popular acts would get slapped with the higher rate. Even classics, such as Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA,” could retail for the higher price. Most of the 10 million songs in the iTunes catalog are expected to remain at 99 cents.

Except, the new pricing model has nothing to do with “supply and demand” economics, which states:

- The more customers want to buy something, assuming a constant supply, the more the price will go up, costing you more dollars, pounds, yen, or whatever.

- If the supply cannot meet the demand for an item, the price will go up until manufacturers can make enough of the item to meet the demand.

- If the supply is too great for the demand for an item, the price will go down until the manufacturers can get rid of their inventory and the supply equals the demand.

Sure, tracks from the most popular acts are in greater demand, but supply isn’t constant or scarce, so there’s no reason for the price to go up. Instead, supply in the digital domain is infinite, which should in fact drive the price down, theoretically to the prize of zero (give and take a little to cover server and bandwidth costs).

As Techdirt concludes: “The actual price [on iTunes] is based on an artificially limited supply and a made up demand” – the aim being to squeeze more cash out of consumers for the minority of music they do pay for rather than reducing prices in order to grow the overall pie.

Or to quote industry commentator Bob Lefsetz, “the key isn’t to get them to pay more for what they do buy, but to get them to pay for what they’ve stolen.” To do otherwise is just plain stupid.

See also: Apple caves to major labels in return for DRM-free iTunes

Although it’s by far the path of least resistance for me (I have an iPod and an iPhone, and I use iTunes every day), I’ve given up on the iTunes store. The Amazon MP3 store is better, but has its own problems (check out the onerous T&C).

Music industry: can I just purchase some music to own at a fair price please? Thanks.

While I don’t disagree with you, let me play devils advocate. Suppose that instead of thinking about the music as being the product, we use attention instead. Consumers only have a limited amount of it, businesses have figured out a way and want to profit as much as they can from it. If someone’s attention drives them to a point where they’ll be willing to pay more, manufacturers will meet that demand by creating product. This is usually done through big marketing campaigns, TV show and movie tie ins, and radio air play. By stimulating consumers interest, the business’ product becomes more profitable and they can charge more. If someone values their time differently or cares more about the less popular bands, then the labels are still able to capture that sale by discounting to provide the value instead. Businesses use price discrimination to squeeze consumers all the time. It’s the reason why matinees and twilight films are cheaper then the 7pm showing. The theaters know that seniors hang out in the mornings why working people come out at night. I’m not sure that their argument violates any economic theory, but I do agree that they’re trying to be greedy.

@Davis Freeberg

Devils advocate is always welcome 😉 I understand your point, but it falls down slightly considering – using your analogy – there are free cinemas open 24 hours a day, showing all the most and least popular films (file sharing sites). That’s the competition.

This isn’t quite right. Since we’re not dealing with a traditional commodity, we can’t just say that supply is approaching the infinite, therefore price should approach zero. You also must consider competition (can they get it somewhere else for less just as easily?) and desirability (how much are consumers willing to pay for it?). Also, this is intellectual property, not groceries that you can buy from any store. There are exclusive contracts involved with artists, agents, publishers, distributors, etc.

Apple only has free-market incentive to lower their price if people are unwilling to pay what they are charging, for instance, if they can get it elsewhere for less money/effort. The same basic rules hold from a sellers perspective in that if sales go down, prices need to follow in order to make money, but if sales are great, you can charge more without hurting your business. This is no different from a lot of IP businesses, like the sale of books or sheet music.

@KPS

“Apple only has free-market incentive to lower their price if people are unwilling to pay what they are charging, for instance, if they can get it elsewhere for less money/effort.”

Most are unwilling to pay and can get it elsewhere – for free. That’s the point. The answer isn’t to raise prices for offering the same but to lower prices and add more value that’s harder to get elsewhere.

As long as there is real competition (read Amazon.com), let the free markets run as they do. I have nothing against variable pricing when there are real competitors in the marketplace.

@ Dale Dietrich

Not sure there is or ever will be real competition as the major labels set the wholesale terms. As a result it looks like Amazon and co. just followed suit:

http://www.last100.com/2009/04/08/more-variable-pricing/

Although ComputerWorld is reporting that Amazon is being favored over Apple as the labels continue to try to weaken Steve Jobs’ grip on the music industry.