Granted, the start of today’s FCC 700 MHz spectrum auction is no spectator sport. No network coverage. No $3 million ads. No pre-game shows.

Granted, the start of today’s FCC 700 MHz spectrum auction is no spectator sport. No network coverage. No $3 million ads. No pre-game shows.

And yet the auction isn’t without intrigue for you and me, although it’s more along the lines of Tammany Hall or a Dick Cheney cabinet meeting. Oh, to be a fly on the wall at AT&T, Verizon, Google, and the Federal Communications Commission, the chief players in the spectrum hunt.

For the most part, nobody yet cares about the 700 MHz spectrum (FCC table) except for teleco geeks, the tech press and bloggers, and the players themselves. It’s too early for any of this to matter at a practical, day-to-day level. But do not underestimate its importance to our lives in the long run, at least here in the U.S.

Our reliance on wireless is growing. In another two years, another billion devices will be added to the 2.5 billion handsets already in circulation worldwide. The growth will be democratic in nature, bringing people together not only in the big cities but in rural areas and developing countries.

Our mobility isn’t slowing down as we lead even more blurred lives, zipping from work to home to kids to church to our own interests, all at the same time. Our dependence on the information that’s important to us is growing, whether it’s email, SMS, photos, MP3s, notes, documents. It’s addicting. It touches a core human emotion, the need to communicate and share knowledge, information, news of the day.

All of this makes the auction even more important because the networks of the future, the ones that will deliver a true mobile Web experience, will be built using the 700 MHz spectrum.

Starting today.

But rather than give you a blow-by-blow account of all the technical details, we’ve taken a simplified look at the auction, the players, why we should care, and what we think the outcome will be.

Setting the Spectrum Table

There are 214 bidders who have been approved by the FCC for the 700 MHz spectrum auction, which starts today and is scheduled to end March 24, with down payments due by April 11.

There are 214 bidders who have been approved by the FCC for the 700 MHz spectrum auction, which starts today and is scheduled to end March 24, with down payments due by April 11.

The bidders are going after 1,200 licenses.

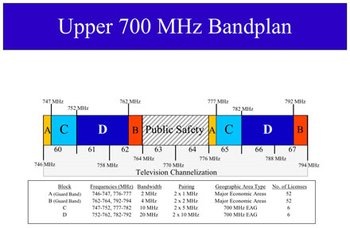

A third of the spectrum is subject to “open access”, meaning the winner must allow any device or application access to any new networks built. This is the spectrum (“C” Block) we are most interested in.

The price tag for this part of the spectrum is expected to be $4.6 billion.

The U.S. government is expected to rake in more than $10 billion from the auction, but with the current downward spin of the U.S. economy, some analysts think the government won’t hit the $10 billion mark.

At the Spectrum Table

The bidders include many of the usual teleco names, particularly AT&T and Verizon, the No. 1 and 2 U.S. carriers, respectively. It’s highly unlikely that AT&T and Verizon — stung by an outsider’s involvement and the sudden interest in “open networks” and “consumer choice” — won’t squash any challenge from other recognizable telecos like Cox Communications, US Cellular, Qualcomm, Alltel, Leap, and MetroPCS.

The bidders include many of the usual teleco names, particularly AT&T and Verizon, the No. 1 and 2 U.S. carriers, respectively. It’s highly unlikely that AT&T and Verizon — stung by an outsider’s involvement and the sudden interest in “open networks” and “consumer choice” — won’t squash any challenge from other recognizable telecos like Cox Communications, US Cellular, Qualcomm, Alltel, Leap, and MetroPCS.

Also at the table — that outsider — is Google, the Internet search giant and online advertising mogul who’s looking to expand its business into the mobile space, not to mention home entertainment and just about everything else humans do. Google’s motivation is obvious: There may be a teeny-tiny amount humanitarian disruption here — we’re helping to upend an entire industry for you, the consumer — but Google smells blood and profit in the water with billions of dollars at stake.

Why Should We Care?

At stake here is what many pundits call the “sweet spot” of wireless spectrum, the 700 MHz frequency vacated by television broadcasters when the industry went all digital. The spectrum promises faster networks (essential for the future mobile Web) and far better reliability (it can penetrate walls and other obstacles).

Tech speak aside, we as consumers should care because it’s quite possibly the last chance to change the U.S. wireless industry for quite some time. Really. The fear is that if the major telecos win, they may make slight changes to the new networks — open access, for example — but they might not go as far as they could in order to protect their turf, Industrial Age business model, and profits.

A new kid of the block, like Google, might seriously disrupt a stodgy, in-need-of-an-overhaul industry. The hope here is that Google will lead a much-needed influx of innovation like new, appropriate handsets developed for our digital, information-intense lifestyles, improved user interfaces and usability, applications we want to use (not what the telecos tell us we can use), freedom to move between carriers using the phone(s) we want, and services we’re not even thinking about but the technology is sitting in labs waiting to be deployed.

Google’s Role

No one except for Google knows what it will do with the spectrum.

No one except for Google knows what it will do with the spectrum.

Will Google bid to win and compete directly with the wireless carriers, building a new nationwide cell network itself? Google has billions stuffed under its mattress, and if anybody can spend nearly $5 billion for spectrum and then an estimated $5 billion a year for several years to build out the network, Google can.

But many analysts don’t see this happening. Google has no wireless experience. It doesn’t have a customer care center, a staple in the telecom business where consumers always seem pissed at the carriers (and for good reason). As the telecos like to say, the wireless industry isn’t the Internet.

The likely scenario is that Google will partner with someone to build a network. But partner with who? AT&T or Verizon? With a carrier who’s not bidding like Sprint Nextel or T-Mobile? With Nokia or Apple? With a smaller player like US Cellular?

Or will Google forgo a cell phone network in favor of blanketing the nation with wireless Internet? After all, Google is leaving the development of the so-called Gphone to members of the Open Handset Alliance it helped form, and Google hopes its open-source mobile operating system Android is a platform that will run on thousands of phones on every network worldwide.

Could this not be Google’s end game? To open up existing and new wireless networks? To get companies working toward new and improved handsets and user experiences based on open standards? To have these devices, many of which may be powered by Android, to prominently feature AdSense, Google search, and the vast array of Google applications from Gmail to Picasa? To help drive down cell phone prices and subscription plans with ad-supported phones?

Verdict

In the end, the 700 MHz spectrum bid is about hope for wireless consumers in the U.S., and maybe worldwide. Hope to end the stranglehold the carriers have over their networks and consumers. Hope for faster networks and the real mobile Web. Hope for better handsets and user experiences. Hope for openness. Hope for newer, interesting services. Hope that it’s not business as usual.

So sit back, watch next weekend’s Super Bowl, and keep an eye on the 700 MHz spectrum auction in the business and technology press. It will have a longer-lasting effect on you than will the New England Patriots or the New York Giants winning the big game.

See also: excellent interactive spectrum map from Portfolio.com.

Thanks for this article it is very usefull for me